This Case Report is Interactive!

Strengthen your understanding of geographic atrophy by answering the challenge questions below.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old woman was referred to us from her local ophthalmologist for a second opinion regarding her age-related macular degeneration (AMD). There were no subjective complaints at this time. She reported that she had been previously diagnosed with arterial hypertension and osteoarthritis. Cardiovascular events were denied.

- The visual acuity was 0.1 logMAR in the right eye and 0.2 logMAR in the left eye with a moderate cataract on both sides.

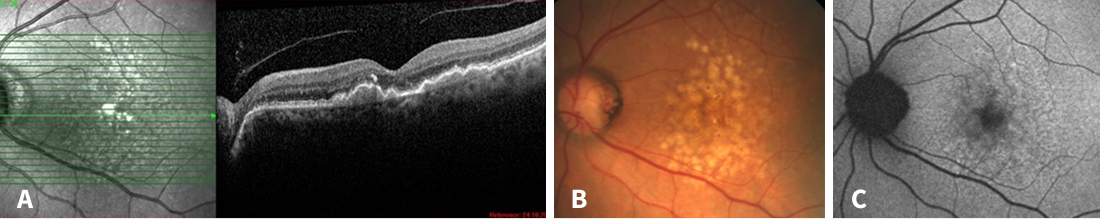

- Initial OCT showed intermediate AMD with soft drusen partly confluent to drusenoid pigment epithelium detachments (PEDs; at least 350 µm in diameter according to AREDS definition) as well as subretinal drusenoid deposits (Figure 1).

- She also exhibited areas of hyperreflective Bruch membrane, consistent with calcified drusen on fundus exam.

- There were several intraretinal hyperreflective foci.

Figure 1. Multimodal imaging at the first visit. A: Intermediate AMD with drusenoid pigment epithelial detachments and hyperreflective foci. B: Fundus photography with yellow-white soft drusen, partially confluent. C: Patchy autofluorescence pattern with no signs of atrophy.

We recommended AREDS 2 nutritional supplements and informed her that her AMD presented multiple risk factors for progressing to an advanced stage, which could lead to impaired vision. The patient also changed her lifestyle, focusing on a healthy, balanced diet based on plenty of antioxidants (mostly blueberries), green vegetables, and fish.

Challenge Question 1/2

Which of the following retinal layers is MOST affected and eventually completely lost in geographic atrophy lesions?

Answer the question above to reveal more case details.

Correct answer: C. Photoreceptor layer

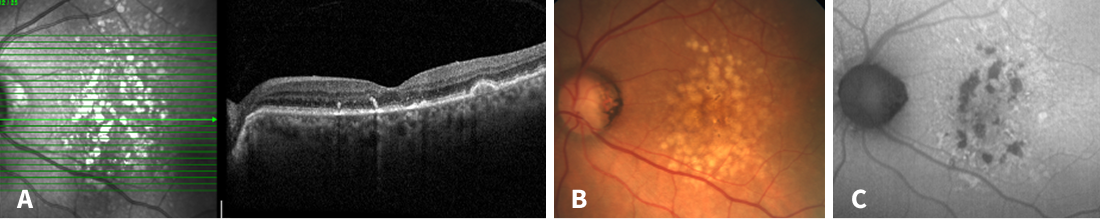

The patient was referred to us 2 years later (Figure 2). The visual acuity was 0.3 logMAR in both eyes. The majority of the drusen and drusenoid PEDs had collapsed since the prior visit. The collapse of the drusen was accompanied only by individual small regions of atrophy. Most of the drusen collapsed without formation of atrophy.

Figure 2. Multimodal imaging 2 years after the first visit. A: Collapse of drusen with partial incomplete outer retinal atrophy (iORA) and incipient signs of geographic atrophy and hyperreflective Bruch membrane, consistent with crystalline drusen on fundus exam (B). C: Several spots of hypoautofluorescence corresponding to small areas of early atrophy.

Challenge Question 2/2

In the absence of scrolled retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) or signs of an RPE tear, which of the following criteria must be present to establish an atrophic area as complete RPE and outer retinal atrophy (cRORA)?

Answer the question above to reveal more case details.

Correct answer: D. All of the above

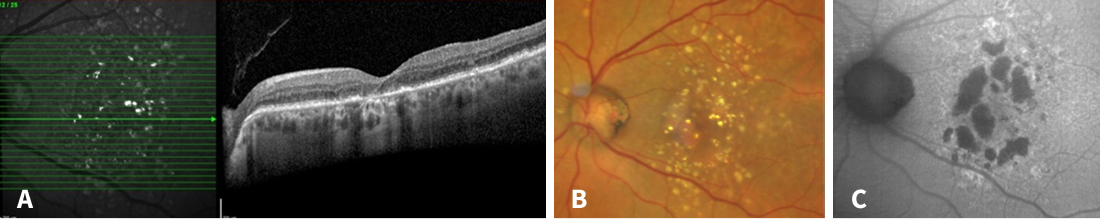

Over the course of the following 4 years, a progressive geographic atrophy (GA) developed (Figure 3), accompanied by a reduction in visual acuity to 0.4 logMAR in the right eye and 0.5 logMAR in the left eye. In Germany, the patient's home country, there is still no approved treatment for GA available. We informed her about currently ongoing disease-modifying drug clinical trials in which our clinic is actively involved. Meanwhile, due to a progressed cataract, cataract surgery was performed, which resulted in a visual acuity of 0.2 logMAR in the right eye and 0.3 logMAR in the left eye.

Figure 3. Multimodal imaging 6 years after the first visit. A: Geographic atrophy had developed with hypertransmission and complete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy (cRORA). B: Atrophic areas now can be seen fundoscopically. C: Hypoautofluorescent spots enlarged indicating an increasing geographic atrophy.

CAUTION: Spoilers ahead!

Finish the interactive case before reading the synopsis below.

Discussion

Atrophy secondary to soft drusen collapse is a known phenomenon. In the vicinity of a drusen collapse with atrophy, a drusen regression without atrophy seems to be possible, and has recently been described as the drusen ooze hypothesis. Here, it is assumed that drusen material is secreted from surrounding drusen via the atrophied area with disrupted pigment epithelium, thus allowing surrounding drusen to collapse without atrophy.1

In 42% of eyes with drusenoid PED, advanced AMD develops within 5 years (19% progressing to GA and 23% to neovascular AMD).2 Eyes with drusenoid PEDs that do not collapse typically have stable visual acuity and stable central macular thickness and should be screened for nonexudative macular neovascularization type 1 by OCT angiography. Such eyes, even if they are asymptomatic, are at high risk of developing exudation.3 Collapsing drusenoid PEDs are associated with a reduction in visual acuity.4

The presence of intraretinal hyperreflective foci is a biomarker for increased progression to advanced stages of AMD, especially GA.5 Subretinal drusenoid deposits are also a biomarker for accelerated progression of AMD.6 Calcified drusen are predictors for fast progression to complete retinal pigment epithelial and outer retinal atrophy (cRORA).7,8 Our patient showed all these characteristics.

This case draws attention to the particular stage of drusen collapse. This deceptive intermediate phase can be misleading. The patient's prognosis appears to be improving, and the visual acuity is usually still relatively stable. Or, if a patient presents for the first time at this (transitional) stage, the findings are often less obvious and require special attention. GA can develop over time and lead to a serious reduction in visual acuity and overall quality of vision. Taken together, a significant reduction in drusen volume on OCT should raise a high level of suspicion for progression to advanced dry AMD. These patients should then be counseled about the ever-increasing spectrum of approved and emerging treatment options.

References

- Monés J, Pagani F, Santmaría JF, et al. Spontaneous soft drusen regression without atrophy and the drusen ooze. Ophthalmol Retin. Published Online First: 2025.

- Cukras C, Agrón E, Klein ML, et al. Natural history of drusenoid pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report Number 28. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:489.

- Sacconi R, Fragiotta S, Sarraf D, et al. Towards a better understanding of non-exudative choroidal and macular neovascularization. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023;92:101113.

- Karabulut S, Kaderli ST, Karalezli A. Long-term outcomes of drusenoid retinal pigment epithelium detachment in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2025;73:843–846.

- Nassisi M, Fan W, Shi Y, et al. Quantity of intraretinal hyperreflective foci in patients with intermediate age-related macular degeneration correlates with 1-year progression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:3431-3439.

- Abdolrahimzadeh S, Di Pippo M, Sordi E, et al. Subretinal drusenoid deposits as a biomarker of age-related macular degeneration progression via reduction of the choroidal vascularity index. Eye. 2022;37:1365.

- Liu J, Laiginhas R, Shen M, et al. Multimodal imaging and en face oct detection of calcified drusen in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Sci. 2022;2:100162.

- Tan ACS, Pilgrim MG, Fearn S, et al. Calcified nodules in retinal drusen are associated with disease progression in age-related macular degeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10.