This Case Report is Interactive!

Strengthen your understanding of geographic atrophy by answering the challenge questions below.

Case Presentation

An 85-year-old man presented at our Macular Clinic at the Eye Center Grischun in Chur, Switzerland, with severely decreased vision in his right eye. The patient was referred to us by a German retina specialist, who previously diagnosed him with advanced geographic atrophy (GA). He was generally in good health with no diabetes or obesity. He was on regular weekly cardiovascular training and did not have any previous history of smoking.

- His visual acuity during the initial visit was 20/100 OD and 20/30 OS.

- Slit-lamp examination revealed a normal anterior chamber with a well-centered and clear IOL.

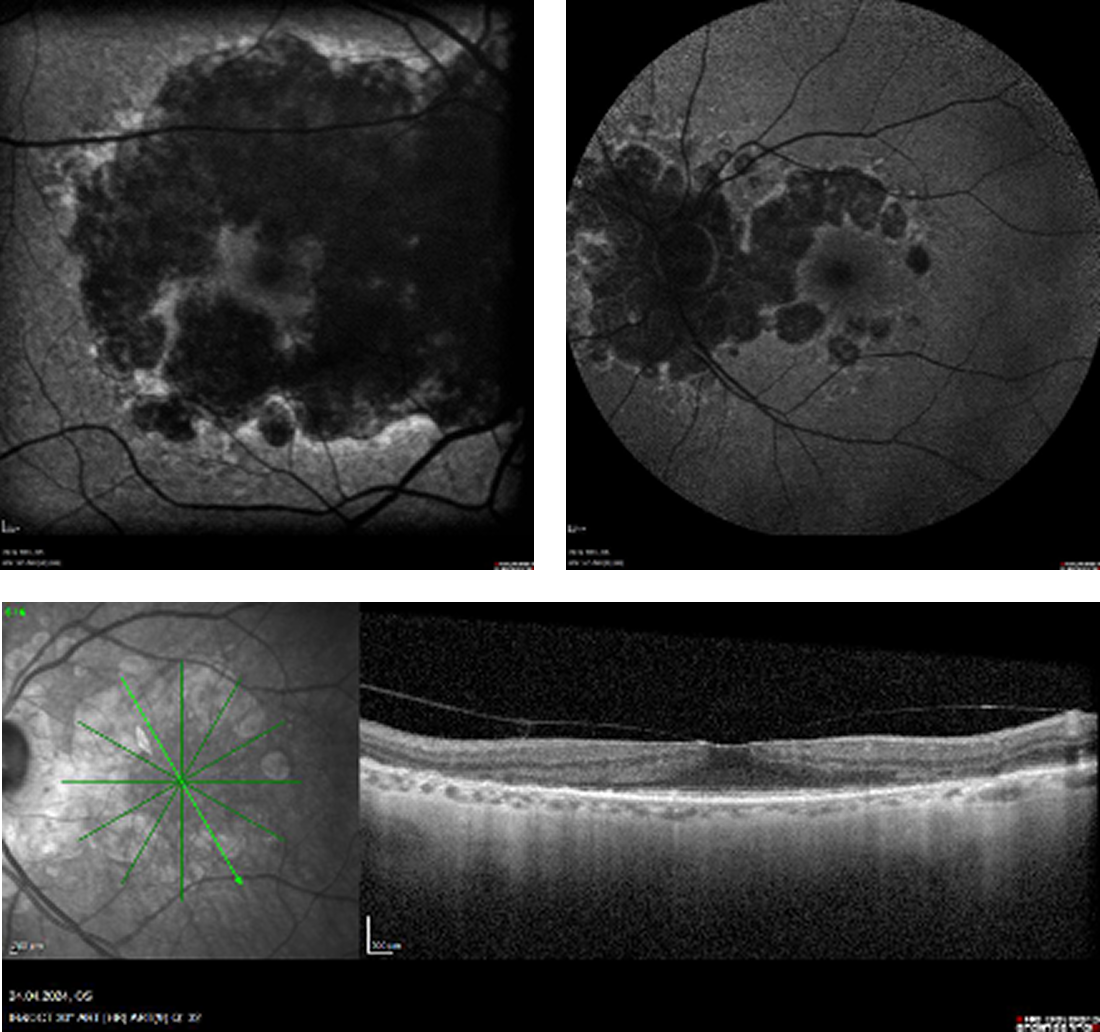

- Biomicroscopy demonstrated advanced age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with GA OU including the perimacular area extending to the foveola in the right eye, while in the left eye, the perimacular retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) remained intact including the foveal architecture. Imaging, including fundus autofluorescence (FAF) and OCT, were used to confirm these findings (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Baseline fundus autofluorescence (FAF) OD demonstrated a confluent nearly extinguished autofluorescence from the upper to the lower arcade affecting the macula. There was limited remaining reflectivity on the foveola. In the left eye, FAF and OCT demonstrated a perimacular GA lesion; however, there was a large perimacular central island with intact retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

We discussed with the patient the status of his eye disease, highlighting that the decline of his reading vision was due to the progressive nature of the GA in each eye. We explained that because the GA lesion in the right eye had already reached the central portion of his visual field, treatment options were limited. Therefore, we focused our treatment discussion on the remaining left eye that still had excellent central vision with intact perifoveal RPE and photoreceptors.

Challenge Question 1/2

Which of the following is hypothesized to be involved in the pathophysiology of geographic atrophy?

Answer the question above to reveal more case details.

Answer: A. Continuous low-grade complement-mediated inflammation

The patient was specifically referred to our clinic in Switzerland to discuss whether complement inhibition therapy might be an option. In his home country of Germany, which is part of the European Union, no complement inhibitor therapies are yet approved by the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EMEA); thus, he was willing to travel to Switzerland where the complement factor C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan (Syfovre, Apellis) has recently become available. In addition to this modality, we also discussed the use of AREDS2 multivitamin oral supplementation, as its use has demonstrated additive protective effects on the progression of GA.1 In our limited experience, oral AREDS2 supplementation and intravitreal pegcetacoplan injections have shown excellent results in selected eyes.

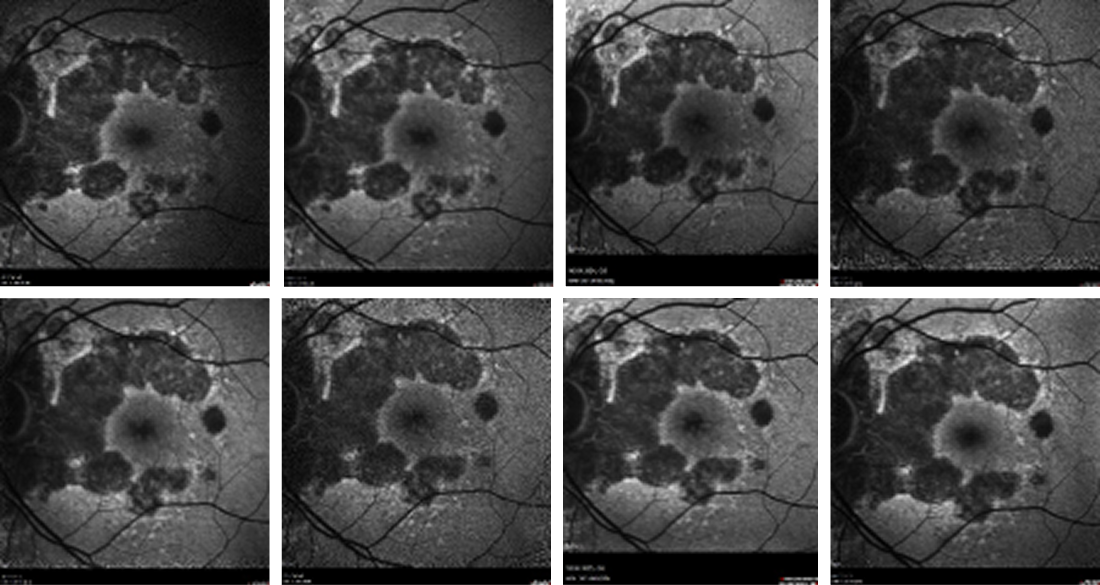

The patient was started on intravitreal pegcetacoplan injections in his left eye beginning in April 2024, and thereafter, monthly for 3 injections. Each visit from Germany included a full clinical examination with slit lamp, biomicroscopy, and OCT and FAF imaging prior to each injection (Figure 2).

Figure 2. FAF imaging of the patient’s left eye taken at each injection visit. Although there was coalescence of the lesions from the time of the first visit (upper left) to the time of the latest visit (lower right), overall, the atrophic area spared the fovea.

There were no side effects associated with the initial three injections. Due to the long distance the patient must travel, and because the patient did not experience any progression of his GA, we decided in June 2024 to extend the inter-injection interval to 6 weeks; this was later extended to every 8 weeks, and the patient has remained adherent to this schedule ever since. Indeed, the patient is very thankful for his treatment regimen and has not complained about the burden of treatment or the need to travel long distances on bimonthly basis. The only issue that has arisen during treatment is that after the 8th injection, his ophthalmologist in Germany noticed moderate asymptomatic intraretinal cystoid macular edema (CME). A similar occurrence of CME was previously observed after phacoemulsification and cataract surgery. Both responded well to topical steroid eye drop application and resolved within 3 weeks.

As of the patient’s latest visit, visual acuity in the left eye remained stable at 20/30. However, in the untreated fellow eye, the GA progressed (Figure 3), and visual acuity declined to 20/800.

Challenge Question 2/2

What is the primary treatment objective with complement inhibition therapy?

Answer the question above to reveal more case details.

Answer: B. Stabilize the disease and/or slow progression

CAUTION: Spoilers ahead!

Finish the interactive case before reading the synopsis below.

Discussion

GA is a progressive vision-threatening disease. In the later stages, as the lesion grows to encompass the fovea, central vision is affected. Although early recognition and education of the patient play an important role, novel treatment options can offer protection and significantly slow atrophic progression. In clinical trials, complement inhibition therapy has been shown to slow the progression of atrophy by 25% to 34%.2,3 Furthermore, longer-term follow-up has demonstrated that patients experience greater benefit (ie, more pronounced slowing of progression) the longer they are on complement inhibition therapy.4,5 However, complement inhibition therapy has not been shown to reverse existing atrophy, nor to restore vision.

In the case of our patient, the loss of central reading visual acuity in the untreated eye demonstrates what could occur if the disease also affects his remaining better contralateral eye. Multiple studies have shown a high degree of concordance between eyes regarding GA incidence, progression, and area.6 It is therefore essential to educate patients about GA, the prognosis for progression, and potential treatment options. If complement inhibition therapy is a consideration, the benefit and burden of treatment must be discussed, as repeated injections are necessary to control the chronic, progressive nature of the disease. The most important motivation for our GA patients to continue their treatment is to maintain their central vision at a meaningful level, giving them an ability to read.

In the past 18 months, we have observed a broad spectrum of responses to complement inhibition therapy. Some patients have discontinued their treatment due to continued disease progression, due to no cost coverage by their insurance company, or because they were unable to return to Switzerland on a bimonthly basis to receive injections. However, the majority of patients have demonstrated good adherence to their treatment regimen, even though most of them must pay out of pocket for the treatment. High-quality service to the patient, flexible follow-up appointments, limited waiting time, and uneventful injections are essential for maintaining patients’ adherence to long-term treatment. Furthermore, it is crucial to dedicate time to present and discuss the treatment objectives and to answer questions to sustain patients’ confidence and trust in this novel treatment option.

1. Keenan TDL, Agrón E, Keane PA, et al; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group; Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Oral antioxidant and lutein/zeaxanthin supplements slow geographic atrophy progression to the fovea in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2025;132(1):14-29.

2. Heier JS, Lad EM, Holz FG, et al. Pegcetacoplan for the treatment of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration (OAKS and DERBY): two multicentre, randomised, double-masked, sham-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2023;402:1434–1448

3. Khanani AM, Patel SS, Staurenghi G, et al; GATHER2 trial investigators. Efficacy and safety of avacincaptad pegol in patients with geographic atrophy (GATHER2): 12-month results from a randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10411):1449-1458.

4. Wykoff CC, Holz FG, Chiang A, et al; OAKS, DERBY, and GALE Investigators. Pegcetacoplan treatment for geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration over 36 months: data from OAKS, DERBY, and GALE. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;276:350-364.

5. Gahn G, Kaiser PK, Khanani AM, et al. The 18-month efficacy of avacincaptad pegol in geographic atrophy: pooled results from GATHER1 and GATHER2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65(7):4400.

6. Boyer DS, Schmidt-Erfurth U, van Lookeren Campagne M, Henry EC, Brittain C. The pathophysiology of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration and the complement pathway as a therapeutic target. Retina. 2017;37(5):819-835.